Bishop Hill

Bishop Hill Defining reality

Dec 16, 2013

Dec 16, 2013  Climate: Models

Climate: Models Science writer Jon Turney has been looking at computer simulations and their role in the decision-making process, considering in particular climate models and economic models. There's a much of interest, like this for example:

Of course, uncertainties remain, and can be hard to reduce, but Reto Knutti, from the Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science in Zurich, says that does not mean the models are not telling us anything: ‘For some variable and scales, model projections are remarkably robust and unlikely to be entirely wrong.’ There aren’t any models, for example, that indicate that increasing levels of atmospheric greenhouse gases will lead to a sudden fall in temperature. And the size of the increase they do project does not vary over that wide a range, either.

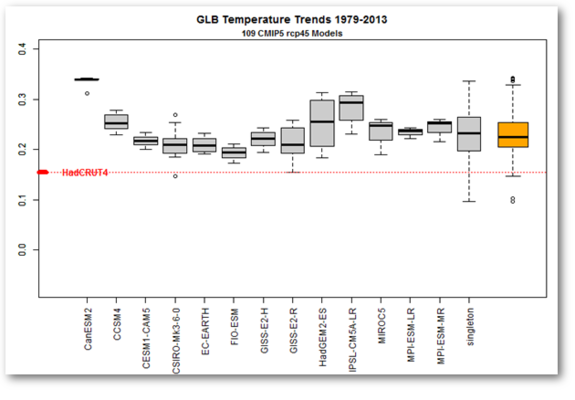

Hmm. Climate models are unlikely to be wrong because they give similar results to each other? Aren't they mean to be tested against - you know - reality? And when you do this, doesn't it show that the models are running too hot?

This isn't the only problem either. Turney cites a suggestion that multiple runs of the same model can help you assess uncertainty:

Repetition helps. Paul Bates, professor of hydrology at the University of Bristol, runs flood models. He told me: ‘The problem is that most modellers run their codes deterministically: one data set and one optimum set of parameters, and they produce one prediction. But you need to run the models many times. For some recent analyses, we’ve run nearly 50,000 simulations.’ The result is not a firmer prediction, but a well-defined range of probabilities overlaid on the landscape. ‘You’d run the model many times and you’d do a composite map,’ said Bates. The upshot, he added, is that ‘instead of saying here will be wet, here will be dry, each cell would have a probability attached’.

But as far as decisionmaking is concerned this misses the point. If there are structural model errors, like the ones we have been discussing in relation to the UKCP09 climate predictions, then multiple runs of the same model are not going to help you.

Turney's article is nicely written and a good introduction to some of the issues, but you might come away with the idea that climate models are a reliable basis for decision making. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Reader Comments (73)

'Unlikely to be entirely wrong'.

We've spent $100 billion over 30 years supposedly bringing these models to the pinnacle of expertise. And yet the best that can be said is that they are 'unlikely to be entirely wrong'.

Somebody somewhere is having us on.....and running off with our cash.

Accidental humor is often the best. These two phrases are very accidental....

"that does not mean the models are not telling us anything"

and

‘For some variable and scales, model projections are remarkably robust and unlikely to be entirely wrong.’

If these clowns were building airplanes or doing any actual productive work.

The money we have given these parasites and con-artists is beyond all belief.

Who would have thought that weather would be an Achilles heel to to permit the con-artists and misanthropes to attack us?

2 + 2 = 3.96... not 'entirely' wrong and when we 'ran it' 50 000 times we got between 3.1 and 3.98 with probabilities attached.

Not entirely wrong being like a woman who is not entirely pregnant.

Seems to me the problem with these 'scientists' is they never learned English, so they attach their own 'probable' meaning to words.

Perhaps they use a model.

"model projections are remarkably robust and unlikely to be entirely wrong": I can only conclude that this fellow hasn't got much experience of comparing model outputs with experimental data.

Merry Christmas Bishop Hill, Josh, and to all blog commentators....And the circles of their minds...

http://fenbeagleblog.wordpress.com/2013/12/16/the-windmills-of-your-mind/

What standards does a model need to conform to in order to participate in the recognised ensembles? Can I write one? Are there criteria for what physical laws and constants are included and what formulae? I am trying to establish to what extent they are bound to come up with a range of answers because they are all conforming to some set of rules which restricts the programmer's freedom, a set of IPCC-defined rules which may exclude the total array of physical possibility.

Second, how bad must the results of any given model be before it is chucked out?

Yes. What the models might be telling him is that all the king's horses and all the king's men are all getting one thing fundamentally wrong. Water-vapour feedback, perhaps? Of course they might also be all too hot for a host of different reasons, or different versions of confirmation bias.

Regardless, whatever the models are telling him, he doesn't seem to be listening.

They don't even understand just how stupid and Unscientific they sound do they?

If it wasn't so serious it would be laughable.

The hands of a stopped clock also '...are remarkably robust and unlikely to be entirely wrong',

and similarly tell us very little about our relationship with our sun.

John B

"2 + 2 = 3.96... not 'entirely' wrong and when we 'ran it' 50 000 times we got between 3.1 and 3.98 with probabilities attached."

That would imply that the models are in the right ball park. We know they're way off reality. A better analogy would be:

2 + 2 = 19... not 'entirely' wrong and when we 'ran it' 50 000 times we got between 17.3 and 21.4 with probabilities attached.

Actually the multiple runs test is usually necessary when you have uncertain inputs in order to determine all possible ranges: It's a simple sensitivity test and is, frankly, absolutely necessary if you are going to use the model to base decisions on. Yes, if the model is basically crap then all the results are crap and you only know that by studying the real world. However, climate modelers don't seem to recognise this basic truth. I asked Gavin if he had ever done a sensitivity test for Giss models and he replied that it 'wouldn't be useful'. I'll bet! It would show that the result obtained is 100% due to the selective judgement of the inputs.

Secondly I have see this weird definition of 'robust' before, ie several models agree with each other so the result is robust. It doesn't make any sense to anyone in any other field unless the models also agree with reality. Implicitly most climate impacts reports are written on the basis that the data must be lying because it doesn't give any scary scenarios. The authors just tack on an inappropriate global model and extrapolate wildly. Yet if there is one thing that everyone agrees on, it's that the global models are of no use for downscaling to local areas. The only way to get something useful is to heavily seed the local boundaries with observational data. The coupled CSIRO pacific model does a reasonably good job of that but it is still not much use for prediction.

Lastly this notion that none of the models produce cooling is total BS. If you load up the aerosol parameter to it's higher levels you can easily get an imminent ice age. I remember Wm Connoley trying that line on me before backtracking with ("no you misunderstand me"). These guys either don't know what they are doing or they assume the listener doesn't (eg most journalists), so they just make stuff up.

As I keep repeating there is a fundamental misunderstanding of how special a beast the climate model is. Invariably, observations are just a possible tool to improve the model. This is the complete opposite of computer modelling in the general sense, where models are a possible tool to understand and replicate observations.

Just look at all the "climate" satellites, each one of them in a relatively low orbit that decays too quickly to allow any climate (multidecadal) observation.

Models rule the whole field of climate science. Why, even when observations go the wrong way, the solution was to stick to the model ("hide the decline").

The fundamental equation of climate science:

unvalidated model = reality

That flood guy gets paid!

I remember being told on a geography field trip in '65 "From here you can see the extent of the flood plain." From this, I deduced at a tender age that if it were to rain very heavily, that which I was observing could be underwater.

But hey, we now live in a digital world. For those that have developed digital brains: have you tried switching them on and off again?

@DerekP

The difference is the stopped clock is correct twice a day, and that fact can be checked and verified

What a piece of nonsense by someone who has never been involved in modelling or simulations!

Is this yet another English Graduate?

According to some sources he is a Senior lecturer in science communication at University College London

His book "The Rough Guide to The Future (Rough Guide Reference)" appears to be another piece of CAGW alarmism!

Martin A: Thanks for the concise summary of the field.

I thought Monte Carlo sims were standard practice in this line of work. Do 'most' modellers really not use them, or is this self-aggrandising clown claiming to have invented it?

"...you might come away with the idea that climate models are a reliable basis for decision making. Nothing could be further from the truth.", not like your economic models predicting 11% cheaper gas in 35 years. Now that prediction is solid of course!

It is a variation of Mosher's bankrupt argument (which he has run at Judy Curry's, among other places) that even though models are not perfect, they are all we have and therefore better than nothing. Therefore we should pay attention.

When I pointed out to Mosher that 300 years ago, all we had was rusty and infected surgical instruments - so were they "all we have and therefore better than nothing" - he suddenly discovered that he needed to clean out behind the fridge, or something.

What a pathetic argument.

Frankly, I think these models will actually turn out to be 'entirely wrong'...

It's all based on policy(UNFCCC) and policy based science(IPCC and national UNFCCC based think tanks).

All the models are based on the UNFCCC because that's where the money is.

It's like the 14th and 15th and 16th century within art. Almost everything painted had to be the Catholic Church conform.

Perhaps someone who knows the working of these models can help with a bit of explanation for me.

I had assumed that the models are provided with a set of input parameters that are directly derived from observational data. They then apply a set of algorithms to simulate how these parameters will evolve over time. Some of the algorithms have well known properties, such as the seasonal variations which tend to cycle every 12 months, and the 11-year solar cyles with a fairly limited degree of variability.

Other events, such as volcanoes, are extremely random - all that is known is the historical range of incidences and intensities, so I assumed that the model run guessed at the likelyhood of such an event at any given time.

What is puzzling me at present is this statement from Professor Bates:

This implies that the models choose a single path through the probability space, with no 'random' element within the run (i.e. no simulated noise) - to get a range of outputs, you provide a range of inputs and parameter sets and run many times.

Surely this makes no sense at all - I would expect that for each run, random events (such as volcanoes) will be simulated using a true-entropy randomising function, using the known spread of possible such events to guess when the event will occur and what impact it will have. In this case, every run would produce different results.

Can anyone explain?

I don't follow all arguments on Climate Etc but I have seen Mosher put forward something more subtle: that all so-called observations or observational results are a product of models of some form. We never in our interactions deal with 'raw data', everything is mediated by what we think is going on. I have no problem with this philosophical view. It doesn't save the AOGCMs from their date with destiny or the strength of Nic Lewis's arguments about sensitivity, as understood by the IPCC. (If you follow Nic closely you will see the pervasiveness of models. Some are more credible than others.)

There aren’t any models, for example, that indicate that increasing levels of atmospheric greenhouse gases will lead to a sudden fall in temperature.

So what? Does Jon Turney really think that it would be impossible to produce a model that predicted a sudden decrease in temperature despite a continued increase in greenhouse gases? Off hand, I can immediately think of two ways in which that could be done. One would be to produce a model based on Svensmark's cosmic ray theory in which a sudden change in cosmic rays reaching the Earth produces a drop in temperatures. Another would be an enormous volcanic eruption, greater than Krakatoa and on a par with Santorini or Tambora creating enough dust in the atmosphere to reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface thereby reducing temperatures for a few years.

If you produce models in which the only significant factor affecting climate change is greenhouse gas emissions then it is somewhat illogical to argue that the models show that greenhouse gas emissions are the only significant factor causing climate change!

I don't think that climate scientists have modelled natural variability such as ocean oscillations, cloud coverage or solar activity, partly because they don't know how to do it and partly because they dismissed natural factors as being insignificant compared to CO2.

I would have thought that the scientific approach would have been to get the basics right before modelling CO2 effects.

I would be pleased if people closer to the science could comment on this.

Yes, I'm very interested in the decision making process, after all what else are these forecasts for.

Is there a trail of where specific forecasts have actually influenced decisions? And are we therefore definitively using unverified models to make those decisions.

For example:

Were Aussie desalination plants built on the back of specific advice using specific model runs predicting drought? If so which ones exactly? Can we see how the original prediction is doing?

Did UK councils not stock enough winter grit on the back of specific forecasts? Again how did the prediction do?

As johanna says this could show that doing nothing would have been preferable to acting on duff models.

And sorry to bang on about my favourite one again, but did anyone receive the 2013 hurricane forecast? (70% chance of between min and max of the last 10 years) If so how did they act (I really can't imagine)?

Or are they just tossed out into the ether to drift away? "In space, can anyone hear you...laugh at a MetOffice forecast!"

steveta

But if you ran the model several times with different inputs then you run the risk of

"not getting the result that you wanted." Which is to be avoided at all costs. :-)

But it is also that many people simply do not understand the purpose of multiple tests, load factors, stress testing etc.

A good example: a few years ago a very senior tester on a project wanted to perform what he called a "stress test" to see how an IT system would react to a heavy load. He set up a harness to bombard a server with database queries. Hundreds and thousands per minute to measure CPU load

What he failed to realise was that all the queries were the same, every time from the same PC. So after the first flurry of CPU activity, all the servers ran the queries from cache and there was no measurable load on the system.

I ran the tests again the next day with a random selection of queries and a periodic flush of the caches and gave him a proper result, which was what he wanted all along.

The moral being that any model or test is only valid if it has a range of inputs and you can see past the first set of parameters.

Simon W - actually, my argument is not quite the way you frame it.

Mosher's argument is about data - that we have to act - and lousy data is better than none. Even if it involves rusty, infected barber's knives, it is better than doing nothing.

My point is quite different. The mere fact that rusty, infected barber's knives exist does not prove a damned thing.

Schrödinger's Cat

But if you accept the hypothesis that the global warming/climate change scare was always developed as an excuse to push for a reduction in the use of fossil fuels by the eco-loons with (as is being suggested elsewhere) the more or less enthusiastic support of the oil companies who saw it as a stick to beat the coal industry with why on earth would you introduce other factors which would serve to undermine the narrative?

I repeat my long-standing mantra: this was always about politics (green and otherwise) and never truly about science. If the major scaremongers really believed the scares they would not be behaving in the way they are, they'd be living in a yurt on top of a high mountain somewhere cool.

at the risk of feeding a troll, in this report, chart 2 shows a very interesting set of circumstances - the way that US natural gas prices compare with European natural gas prices over the last 8 years. It even explains the evolution of prices...

http://www.eulerhermes.us/economic-research/economic-publications/Documents/economic-insight-petrochemical-europe.pdf

do the models use positive feedback? if so then they can produce any ammount of warming or cooling according to the settings for the internal parameters

ie the model output merely reflects the beliefs and prejudices of the modeller

so, no models show cooling? well, hardly a surprise!

ps who checks the code for bugs?

johanna:

I have trouble parsing that bit in the middle. But I also have a problem about you fighting a proxy war against Steven Mosher in a place that he might not read or wish to enter debate. Earlier you said of him:

I dislike dissing the reputation of a real person (who happens to have contributed a great deal to the cause of good science in my view) from someone who pays no reputation price even if she's shown to be wrong about the matter in question. I don't think you should have mentioned Mosher at all, to be clear. If you feel you have to outline what you think is his argument, do so as 'someone said'.

On the other hand, if Steve is reading and wants to chip in, no problem!

THE MISUNDERSTANDING OF THE NATURE OF MODELLING

Its interesting to see how often the reliability of model results is misunderstood. I am an experienced 3D modeller (though quite some years since I ran a model myself). I am working with a team running a hydrological model. They've put days and days of work into it.

The problem is, for them the model is giving the 'wrong' result. It gives a negative result instead of the expected positive. What do they conclude? 'There's something wrong in the model. We will keep working on it and adjusting or adding parameters until its working better.' That sounds kind of logical.

But, if the first model runs had given somewhere near the answer they expected, they would have concluded it was ok - regardless of whether the parameters were correct or not!

That is the nature of modelling, and we see it with the climate models. They all eventually give a temperature rise within an expected and plausible range that fits the theory. If a model shows a temperature drop - something's wrong. If it shows a very large temperature rise over 100 years (say +100 degC) - something's wrong. So modellers keep tweaking their parameters until the model gives an expected and 'right' answer.

This does not mean models are not useful. They can be very useful. But their main use is showing whether your selected parameter values and theory are plausible, not whether they are fundamentally correct.

It is worth noting the differences between the hydrological model and GCMs being discussed.

1 - The hydrological model can reasonably be compared to observational data in a realistic time frame. As such, model development can be iterative, in the same way as with weather models - compare your model output to reality often enough and you can improve the reliability and accuracy of the model. GCMs can only be proved right or wrong over a period of several years, by which time the model ahs been superseded anyway.

2 - The hydrology model is much more reasonably described as 'physics based' than are the GCMs, which are a hodge podge of some reaonsably well constrained physics (e.g. IR absorption properties of CO2), some 'educated guesses' (e.g. effects of aerosols), some things that can only ever be parameterised (coloud and storm formation) and some elements of WAG (volcanic events etc).

3 - The amount of computational power needed to run the models to completion. Obviously, if the hydro model can be run 50000 times, it is reasonable to vary the range of start conditions quite widely and so it is likely that model space and reality overlap.GCMs are far more computationally intensive, so very few reus are possible, while the range of input parameters is much wider. As such, it is very difficult to demonstrate that model space and reality bear even a passing resemblance.

As for Dr Knutti's comment that the models agree with each other, that holds little weight if the models are not truly independent. To use an analogy from my geochemical work, if I and a colleague both prepared a sample using the same reagents and technique (method X), the difference in our results tells us something about the precision of the method but nothing about the accuracy - we could be getting good agreement around a completely wrong result (bias or inappropriate method). If my colleague undertook the testing by an entirely different technique (method Y) and obtained comparable results I would have some more reassurance on the reliability of each technique. And then if another bunch of analysts came up with similar results using tehcniques A, B and C, I'd have good confidence in the accuracy of our results. My impression is that climate modelling is more like method X compared with method X and a bit, so with little independence.

The recent NIPCC report, Climate Change Reconsidered II, has page after page on model failures and limitations in the chapter on models. Free download here: http://heartland.org/media-library/pdfs/CCR-II/Chapter-1-Models.pdf

I remember back in the 1970s when climate models were treated a bit like circus acts. Hey, look!, here's one that can do an ice-covered earth and it takes ages to get back out from that! What a hoot!, and that sort of thing. Getting a dog to walk on its hindlegs attracts oohs and ahs, and it doesn't have to be done well (as Johnson observed way back in the 18thC) in order to provide some amusement or even slightly impress the viewer.

I presume the models are a bit better nowadays. They'll certainly be bigger and have more bells and whistles, but it seems clear that they are well away from being fit for decision making or planning. The fact that they underpin the climate projections on which so many local authorities and government departments seem to take as gospel is a source of considerable concern. The list of key assumptions behind the UK official projections should by itself raise eyebrows:

See: http://ukclimateprojections.defra.gov.uk/22537"

Truly, future generations will be astonished. Hopefully, they will still be wealthy enough, and past the worst of the harm we are inflicting with such lunacies as the Climate Change Act in the UK, to be amused as well.

John S

"Main assumptions

That known sources of uncertainty not included in UKCP09 are not likely to contribute much extra uncertainty.

That structural uncertainty across the current state of the art models is a good proxy for structural error.

That models that simulate recent climate, and its recent trends well, are more accurate at simulating future climate.

That single results from other global climate models are equally credible.

That projected changes in climate are equally probable across a given 30 year time period.

That local carbon cycle feedbacks are small compared to the impact of the carbon cycle via change in global temperature."

Is that supposed to be science?

Mike Jackson 3:27PM

You could well be right. The climate scare was hijacked by so many different interest groups almost immediately that it could easily have been started by one of them. I would be interested in a reference to "elsewhere".

Going back to the models, the climate scientists have provided nearly two decades of proof that they don't know how to model our climate. It amuses me when they have big debates about whether the climate sensitivity is 1.8 or 2.2 or whatever, when we know that the models used to do the calculation are wrong. Many people seem to have lost sight of reality in favour of model outputs.

Check with reality surely not.

Models can be very useful tools. When the system is understood and the model has been validated it becomes a marvellous tool to aid decision making. When the system is poorly understood, the model aids exploratory thinking though this must be handled with care because plausible results are not necessarily an indicator of validity.

Climate science has muddled everything up, using a clearly flawed model of a highly complex and poorly understood system and presenting the conclusions as gospel and as the basis for policymaking. This is almost criminal, really.

However, the situation is made much worse because ever since the early stages, the scientists have publicly insisted that carbon Dioxide will lead to catastrophic global warming. These are the people who set the initial conditions and the choice of variables as well as the relationships between the variables in the climate models. They are hardly going to be truly objective.

Now, after years of getting it wrong, the scientists are adamant that their models are still correct, even though normal scientific practice would involve a fundamental re-think of the importance of CO2 with respect to other natural drivers.

We therefore have the extra complication of scientists in denial, desperate to tune their models to provide an explanation for the pause whilst still promising a catastrophic future. All of this is being performed in public. They are just amazingly fortunate that the public, politicians, academia and the establishment still seem to be blind to this abuse of science.

Seems the

Indiansscientists are collecting models like crazy...These people are defiling reality, contaminating it with make-believe.

It is a variation of Mosher's bankrupt argument (which he has run at Judy Curry's, among other places) that even though models are not perfect, they are all we have and therefore better than nothing. Therefore we should pay attention.

(...)

Dec 16, 2013 at 2:11 PM Johanna

I have seen that argument a number of times, although I can't remember if it was Mosher or others who proffered it.

I think it misses a key point, along with, so far as I can see, pretty well all climate science models (GCM's, "radiatiative forcing" computations).

A model that has been validated, even if not perfect, can have numerous important practical uses. Information system performance analysis, telecommunication system traffic modelling, nuclear reactor dynamics, spacecraft guidance, and so on and so on.

BUT a model that has not been validated, if you believe and act on its results, is worse than having no model at all and simply saying "sorry we just don't know". This elementary principle has, in the groupthink world of climate science, faded into invisibility.

A further delusion in climate science use of models is the belief that a new model has been validated if it produces results similar to previous models (which are based on similar assumptionsand ignorance of similar aspects of the physical system). I think that the Nic Lewis graphic reproduced above by the Bish illustrates this.

Yet another fallacy in climate models is "testing on the training data" ie arguing that since a model can reproduce a short section of climate history, it has been validated. This is claimed even though climate data from the same period was used in "parameterising" it *. I can produce a model that reproduces past climate perfectly yet incorporates no knowledge of the physical effects involved and therefore with no capability to predict future climate changes.

The Met Office has stated in its publications that climate models are the only way to predict climate changes.

* Parameterising is replacing the representation of a physical effect too poorly understood to model properly, by a simple formula with a few parameters selected to fit the observed data.

This is an important topic because it deals with the heart of the CAGW flaw - the reliance on models that have not been validated. This is perhaps the Achilles heel of climate science. Someone should challenge Walport as to why he advises the government to base policies on a model that has not been validated. If he claims it has been validated, ask for the proof. I cannot imagine how any of these models could ever be validated when you consider the huge divergence from reality.

What, if anything does the Met Office say about validation? Perhaps RB could comment.

As we discovered in the recent thread 'Making Fog' the modellers decide in advance what is realistic and only seek to model that so any prejudices that they may have will be manifest in their outputs which is why they all run hot. Modelling is nothing more than self-affirming assertion with a very large ticket price.

@John B

A better analogy would be:

2 + 2 = 19... not 'entirely' wrong and when we 'ran it' 50 000 times we got between 17.3 and 21.4 with probabilities attached. </I>

Actually, it's:

2+2=19 - our model shows this to be quite correct as we are assuming that a number somewhere around 15 (+/- 40) is hiding behind that cupboard over there....

This is a flat out lie, else the guy doesn't know what he's talking about.

Defining reality

Sharp is ceasing solar panel production at its Welsh factory with the loss of 250 GREEN jobs.

Tesco have a trial of infra red cameras at the doors of some of their stores, the hope is that they can run a model that will tell them when they need to open more tills for queuing customers, up to present, customers are still queuing, or not queuing, Tesco say they haven`t worked out the maths yet.

How chaotic are customers coming into a tesco store collecting groceries and paying for them compared with the climate system.

To re-state the obvious. The models will never improve. They are required to produce a range from reality to catastrophe.