This is a question that has been bouncing round in my head, probably for years. Maybe I've been visiting too many libertarian blogs. But then again, maybe there's something in it. We'll see.

A couple of things prompted me to write all this down. Firstly a line in Jan Morris's recent article about civil liberties on Comment is Free and secondly an article on gun control by an American campaigner called Dave Kopel.

Morris first.

Even the middle classes, once the very backbone of robust individualism, are not immune to the contagion. They all think twice about expressing their views in case they say something that is politically incorrect.

She might as well have been speaking about me, because the idea that gun control might be behind our loss of civil liberties is deeply, deeply politically incorrect. It's an idea which is likely to get one labelled as a "nutter". A couple of years ago, I couldn't have imagined holding this kind of belief. But perhaps things are changing, now the civil liberties debate is in full flow, and maybe it's time to try the idea out for size. We'll see.

Morris goes on the predict our eventual decline into submissiveness and eventually into totalitarianism.

A few more generations of nagging and surveillance and we shall have forgotten what true freedom is. Young people will have foregone the excitements of risk, academics will temper all thought with caution, and the great public will accept without demur all restrictions and requirements of the state. Ours will be a people moulded to docility, perfect fodder for ideologues.

And you can see it happening all around you as the surveillance state grows, and freedoms that we once took for granted are legislated into the history books. It really is time to make a stand.

And what about Dave Kopel? Kopel is a libertarian writer and researcher; he was formerly professor of law at New York University and the [Update: an assistant] attorney general for the state of Colorado. Clearly then, he is a man of some intellectual stature. However he is also a prominent supporter of the right of the American public to carry firearms and his stand on this issue would surely lead a majority of people in this country to categorise him as a "gun-nut". I'm sure I am doing myself no favours by mentioning his ideas on this side of the Atlantic, but as I said, perhaps people might now be ready to consider a different view. We'll see.

Some weeks back, I came across an article Kopel co-wrote with another lawyer called All The Way Down The Slippery Slope: Gun prohibition in England and some lessons for civil liberties in America (link). Like Jan Morris, Kopel also sees Britain ceasing to care about civil liberties - he describes how a people can lose what he calls their "rights-conciousness". He then tries to explain this in terms of the history of gun control in the UK.

After tracing the history of gun ownership from its nineteenth century apogee to full prohibition today, Kopel sets out the effects of the ban on civil liberties in Part IX of the essay. Although his view is that gun prohibition in Britain was not behind the loss of civil liberty, he doesn think that it played an important part:

[A]ll civil liberties in Great Britain have suffered a perilous decline from their previous heights. The nation that once had the best civil liberties record in Western Europe now has one of the worst. The evisceration of the right to arms has not, of course, been the primary cause of the decline, although, as this Essay will discuss later, it has played a not inconsiderable role. More generally, the decline of all British civil liberties appears to stem from some of the same conditions that have afflicted the British right to arms.

This section of the essay is worth reading just to feel the sense of incomprehension that Kopel has as he reels off the list of restrictions on their liberty that the British have allowed their rulers to inflict on them.

While Kopel makes a strong case against what is currently being called the salami slicing of civil liberties, his thesis that gun control hasn't been a primary cause is starting to seem to me to be wrong, at least for some of the civil liberties problems we face.

Take CCTV. Our city streets are, by common consent, violent, dirty unpleasant places for the most part. Only young strong men are likely to feel safe in many parts of the country, and then only if they are in a gang. As Justin Webb's recent article on violence in America made clear, American streets just aren't like this.

Why is it then that so many Americans - and foreigners who come here - feel that the place is so, well, safe?

A British man I met in Colorado recently told me he used to live in Kent but he moved to the American state of New Jersey and will not go home because it is, as he put it, "a gentler environment for bringing the kids up."

This is New Jersey. Home of the Sopranos.

Brits arriving in New York, hoping to avoid being slaughtered on day one of their shopping mission to Manhattan are, by day two, beginning to wonder what all the fuss was about. By day three they have had had the scales lifted from their eyes.

I have met incredulous British tourists who have been shocked to the core by the peacefulness of the place, the lack of the violent undercurrent so ubiquitous in British cities, even British market towns.

"It seems so nice here," they quaver.

Well, it is! [...]

Ten or 20 years ago, it was a different story, but things have changed.

And this is Manhattan.

Wait till you get to London Texas, or Glasgow Montana, or Oxford Mississippi or Virgin Utah, for that matter, where every household is required by local ordinance to possess a gun.

Folks will have guns in all of these places and if you break into their homes they will probably kill you.

They will occasionally kill each other in anger or by mistake, but you never feel as unsafe as you can feel in south London.

It is a paradox. Along with the guns there is a tranquillity and civility about American life of which most British people can only dream.

Webb is clearly surprised by this, but he deserves praise for telling it as it is. To Americans it's probably less of a shock.  The science fiction writer Robert A Heinlein was pointing out the connection between civility and arms as far back as 1942, when one of his characters opined that "an armed society is a polite society". And when you think about it, the paradox that Webb sees is only on the surface. As soon as you realise that noone in their right mind would get aggressive with or be rude to someone carrying a gun, it all becomes painfully obvious.

The science fiction writer Robert A Heinlein was pointing out the connection between civility and arms as far back as 1942, when one of his characters opined that "an armed society is a polite society". And when you think about it, the paradox that Webb sees is only on the surface. As soon as you realise that noone in their right mind would get aggressive with or be rude to someone carrying a gun, it all becomes painfully obvious.

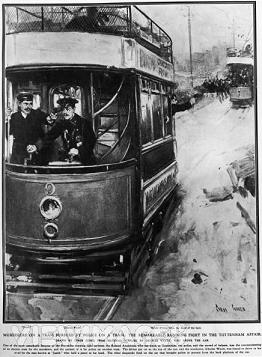

So in America, an armed people has retained old-fashioned manners and old-fashioned civil liberties. This is the common law approach to public order that we used to have here. Civil society was responsible for law and order, and every member of the public was required (that's required, not advised) to intervene if they saw a crime being committed. Perhaps partly because of that requirement people were able to carry arms for their defence.  An article from the Telegraph from a few years back tells the story of a group of Latvian anarchists who attempted a wages robbery in Tottenham. Their intended victims fought back and they were forced to flee, pursued across London by a posse of doughty citizens, both armed and unarmed, who eventually apprehended them. (The police had lost the key to their gun cupboard, and were unable to assist).

An article from the Telegraph from a few years back tells the story of a group of Latvian anarchists who attempted a wages robbery in Tottenham. Their intended victims fought back and they were forced to flee, pursued across London by a posse of doughty citizens, both armed and unarmed, who eventually apprehended them. (The police had lost the key to their gun cupboard, and were unable to assist).

This is how it used to be. However it simply doesn't happen like this any more. In the twentieth century we took an entirely different approach to firearms, with the freedom to go armed being steadily eroded by means of successive small legislative and administrative steps - what is now called "salami slicing". First there was licencing and registration, and then tighter and tighter restrictions on who could have a gun, followed by tighter and tighter restrictions on what guns they could have, and how many, and how they had to store them. Eventually the populace was entirely disarmed, and now society can only fall back on the police for its defence.

The first thing to notice about this process is that it has reduced the number of law enforcement officers on the streets to a tiny fraction of what it was. In the nineteenth century, as we've seen, every adult was responsible for upholding the law and preventing crime. Now we are, quite correctly, advised to leave all this to the police - obviously they are now the only ones with the wherewithal to come out alive from a brush with the criminal classes.

With such a devastating loss of policing manpower, there is now a fleetingly small chance of a law enforcement officer being on hand when a crime is committed. This in turn has meant that the former state of affairs, where the law could intervene as a crime was committed or soon afterwards, has become impossible to pursue with conviction any longer. There is simply not the manpower to do so. With a horrible inevitability, the state has had to try to convince criminals not to commit crimes in ways other than presenting them with a risk of being caught in the act.

The traditional way of doing this was of course to make the punishments severe enough to discourage people, but with much of the middle classes persuaded that long prison sentences were illiberal, this approach too has suffered. Capital and corporal punishment have likewise fallen by the wayside, and because of the same erroneous presumption that such punishments were irreconcilable with liberalism.

As a result, the state has had to resort to methods used in places where the state doesn't have the confidence of the people. It has taken on all the powers of surveillance that we would associate with a police state - CCTV, DNA database, warrantless searches, fingerprinting children, ID cards, in a desperate bid to convince criminals that the risk of being caught is so high as to make the effort pointless. But with prison sentences handed out so sparingly, and so regularly cut short by parole boards, the criminal classes are simply not convinced that the risks outweigh the rewards. They know where the CCTV cameras are and the crime wave simply shifts to somewhere less overlooked.

As a result, the state has had to resort to methods used in places where the state doesn't have the confidence of the people. It has taken on all the powers of surveillance that we would associate with a police state - CCTV, DNA database, warrantless searches, fingerprinting children, ID cards, in a desperate bid to convince criminals that the risk of being caught is so high as to make the effort pointless. But with prison sentences handed out so sparingly, and so regularly cut short by parole boards, the criminal classes are simply not convinced that the risks outweigh the rewards. They know where the CCTV cameras are and the crime wave simply shifts to somewhere less overlooked.

Looked at this way the root cause of the wave of authoritarian legislation which threatens to swamp us is not authoritarianism so much as "woolly liberalism". We won't punish criminals adequately, so we get more criminals. We won't allow the law-abiding to uphold the law, so our streets get swamped with CCTV. Witnesses can't defend themselves guns, so we have to allow anonymous evidence in court. Women can't defend themselves from rapists, so they shouldn't go out alone. The opinionated can't defend themselves from retribution, so better to legislate them into silence.

We find ourselves between the horns of a dilemma. The idea of rearming the populace is greeted by most "right-thinking" members of the middle classes as evidence of a kind of madness, an idea to get you cast out from polite society. "We don't want to end up like America", they will say, as they check the locks on their doors and windows, and test the burglar alarm one more time.

But the alternative is to continue our increasingly precipitous slide down the slippery slope that ends up with the UK resembling North Korea.

America or North Korea. You decide.