I've been reading a bit about aerosols in recent days. As many BH readers will know, these are one of the great uncertainties in the Earth's climate and so they crop up all the time.

This interest was provoked in part by a conversation I was having with Ed Hawkins about his new paper. I had invoked Bjorn Stevens' study from which it is possible to infer a value of -0.5 Wm-2 for the overall effect of aerosols, around half of the IPCC's best estimate of -0.9 Wm-2. This of course would imply that climate sensitivity would have to be much less than the IPCC suggests it is.

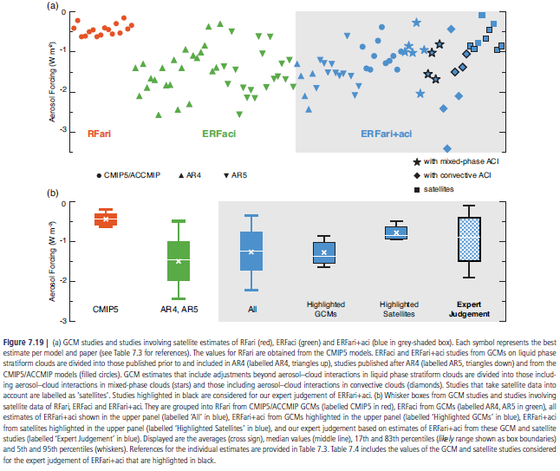

Ed suggested that I was cherrypicking a single paper that gave me the answer I wanted, and I wondered what the range of estimates was. Here is Figure 7.19 from the Fifth Assessment Report (click for a slightly larger version), which shows the observational estimates from satellite measurements and the various GCM estimates ("with physics in") and how these are combined using "expert judgement" to give the best estimate of -0.9 Wm-2.

We are interested in the two grey boxes on the right, which show the total of the direct and indirect effects of aerosols. In the top box, the markers with black borders are the subset selected for the expert judgement. The squares are the satellite estimates, and as you can see they are all packed into a corner, with none of them below -1 Wm-2 and some considerably closer to zero. The GCM estimates - the diamonds and stars - are all over the place, which is not surprising when you realise that the effect of aerosols is intimately bound up with clouds, which are little understood and cannot be properly modelled in a GCM.

So it is similarly unsurprising that by the time you get to the expert judgement subsets in the lower panel, there is a startling lack of overlap between observations and GCMs.

This kind of thing might have led more traditionally minded scientists to question the validity of the GCMs - the observations trumping the hypotheses as in other fields of scientific endeavour. But this being the IPCC, we get instead an "expert judgement" combining the observations with the hypotheses, in a process that seems to neatly mirror what happens on the climate sensitivity side of the equation.

This is particularly worrying in the light of Bjorn Stevens' thinking on these questions. Stevens' headline finding was that aerosol forcing values more negative than -1 Wm-2 were implausible. If he is correct, the majority of the GCM estimates of aerosol forcing would have to be junked. Stevens had several lines of reasoning for this conclusion, but one of his observations was that the temperature history of the past was quite hard to reproduce with a strong aerosol forcing. So in the first decades of the twentieth century, when there were lots of aerosols around but relatively little greenhouse gas forcing, we should not have seen any warming. But in fact that is just what we saw, with the planet warming from 1900 to 1940. In similar vein aerosols, being shortlived, should mainly effect the Northern Hemisphere where they are produced, particularly in the early part of the temperature record when the effect would be most pronounced. Again, this is not what is seen in practice.

Now undoubtedly there are issues with the satellite observations - with several adjustments required to reach a final figure. I haven't yet investigated the uncertainty bounds involved in these studies, which might, if very wide, provide some justification for what the IPCC has done. But with the satellite best estimates so tightly grouped one can't help but pick up something of a stench from Chapter 7 of the Fifth Assessment Report.