There are two interesting posts advocating carbon taxes doing the rounds at the moment. These have been getting quite a lot of attention because they have been written by libertarians rather than the millenarian hippies and the retired Socialist Worker salesmen who usually promote the idea. I shall hazard a comment on these economic issues, issuing my customary caveat that economics is not really my thing.

First up is Jonathan Adler, who normally blogs at US law blog, the Volokh Conspiracy, but has chosen to set out his ideas at Megan McArdle's blog:

It is a well established principle in the Anglo-American legal tradition that one does not have the right to use one's own property in a manner that causes harm to one's neighbor. There are common law cases going back 400 years establishing this principle and international law has long embraced a similar norm. As I argued at length in this paper, if we accept this principle, even non-catastrophic warming should be a serious concern, as even non-catastrophic warming will produce the sorts of consequences that have long been recognized as property rights violations, such as the flooding of the land of others.

The other is by Tim Worstall, here at the Telegraph blog:

So this is what we know about climate change. We know there will be some effect from emissions, and we also are uncertain about what that effect will be. The uncertainty itself means that we should do something. But what?

I've already explained this here. Don't listen to the ignorant hippies to our Left, or to those shouting that there's nothing to it from the Right. The answer is, quite simply, a revenue-neutral carbon tax.

The idea of a revenue-neutral carbon tax, with the proceeds distributed on a per-capita basis is enticing, to the extent that it is less obviously corrupt than all the other measures that are currently in place. And as Tim Worstall points out, the cost of all these other measures is in the UK is already in excess of what a carbon tax based on a sensible estimate of the cost of carbon is. The introduction of the tax would therefore presumably not only lead to the demise of the renewables obligations and subsidies to windfarms and the like (pull the other one, I hear you say) but would also bring about a rise in other taxes to make up the shortfall.

The real cost of carbon or the cost that is good for us?

The carbon tax as envisaged by most of its proponents would involve taxing carbon as it was extracted from the ground as oil or gas, and returning the proceeds on a per-capita basis. In essence we have a exercise in redistribution from heavy carbon users (the rich) to light carbon users (the poor). The amount of this redistribution is therefore a direct function of the cost of carbon; redistribution from rich to poor becomes not a question of morals but of climate science.

Which would be pretty strange.

Although Timmy suggests that the figures involved are relatively small ($80/t CO2 on Stern's estimate), readers here know that estimates for the cost of carbon range as high as the $1000/t or more put forward by Ackerman. At that level, American redistribution via the carbon tax would be $18000 per capita per annum. We could call it carbon communism.

But wait a minute, I hear you say, Ackerman's figure is insane - and indeed it is. However, we have seen the figure touted by establishment figures in the UK, and Ackerman is a co-author on James Hansen's upcoming paper. What you or I might think of as mad and without any basis in reality is accepted as sound by any number of people in positions of influence. Stern's figure seems dubious to many people too. It is well known that his estimate involved all sorts of jiggery-pokery, with discount rates picked to give the answer that he felt was "moral".

How then can members of the public be sure that the figure arrived at is an estimate of the true cost of carbon rather than a reflection of what a bunch of millenarian greens in the academic firmament feel is good for us? The answer is, we can't. Right along the chain from climate model to carbon cost estimate society would rely on academics who have shown themselves to be utterly unscientific and devoid of any integrity and a process that is so corrupted by political activism as to make it meaningless for policy purposes. We cannot hand over control of part of the taxation system to people like this without means to enforce professional behaviour and to ensure the process is unbiased.

The problem is that the corruption of science now runs so deep that I fear it is beyond repair. In climatology, where materials and methods are routinely kept secret, where journal gatekeeping goes unremarked, and where the funding streams are directed by environmentalists and millenarians, there is little hope of ever actually achieving an estimate of the cost of carbon that is not distorted to the point of meaninglessness.

Who am I hurting?

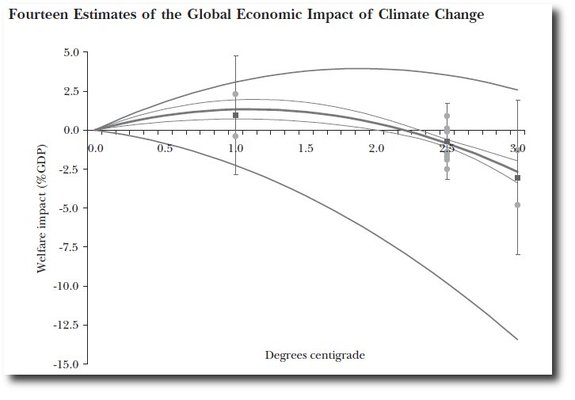

Here's another issue. The economists' estimates try to put a cost on carbon emissions that captures all the costs and benefits forever (discounting future costs and benefits in some way). However, economists also agree that the effects of global warming are likely to be positive for warming of up to 2°C above current levels.

As the chart shows, there are two estimates for the effect of relatively small warming - one positive and one negative, but Tol, from whom the graph is sourced, tweeted the other day that the author of the study predicting negative consequences has since changed his mind, so it appears that there is now a consensus (of sorts) that small warming will have beneficial effects for mankind (but see all the caveats above about whether we should believe any estimate based on climate science).

Think about the implications of this. If we are to believe the IPCC's central estimate of future warming of 2°C/century, then for the next hundred years - which is to say at least for the rest of my lifetime - I am on average increasing the value of my neighbour's property, not damaging it. I'm not sure I can accept being punished with a carbon tax for doing this.

So what am I saying?

A revenue neutral carbon tax is, on the face of it, a better policy instrument than anything tried so far. The problem is that it will almost certainly not be revenue neutral and it will probably reflect an millenarian view of the cost of carbon. It is therefore hard to say for certain if it will be any sort of an improvement on the shambles we have now.